Haiku Society of America Haibun Awards

Haibun Awards for 2021

Margaret Chula & Bob Lucky

judges

We received a record 173 entries this year, which shows an increased interest in writing haibun. Submissions in this year’s contest included everything from rhymed quatrains and rap to free verse and prose poetry, from flash fiction to brief travel accounts.

Our process was slow and thorough. We had the added challenge of being in different times zones—the Pacific NW and Portugal—eight hours apart. We were both in agreement on the necessity for synergy between the prose and haiku as well as the importance of a unifying title. For the prose, we looked for a unique voice and emotional resonance. For example, we were impressed by the short dialogue at the end of “Air”, which enlivened the prose. Present tense can also bring a sense of immediacy, inviting the reader into your story. Using strong verbs and a few well-chosen adjectives also serve to create effective prose. Nouns that do double duty, such as “bristlecone” and “lobelia,” bring other associations to mind. All the haiku in the winning haibun contained a reference to nature. They expertly shifted away from the prose, adding new meaning to the narrative. Interestingly, all three of the top prizewinners had one-word titles. After rereading the entries several times, we each compiled a shortlist of fifteen. Happily, many of our choices overlapped. We then winnowed it down to eight and defended the ones we differed on. The top three winners changed daily. In the end, we chose haibun that we found ourselves returning to for enrichment, insight, or pleasure.

We would like to thank the Haiku Society of America for inviting us to judge this contest and Chuck Brickley who guided us through the process. Most importantly, we would like to thank all of you who offered your haibun to be judged—an act of courage and trust that we admire.

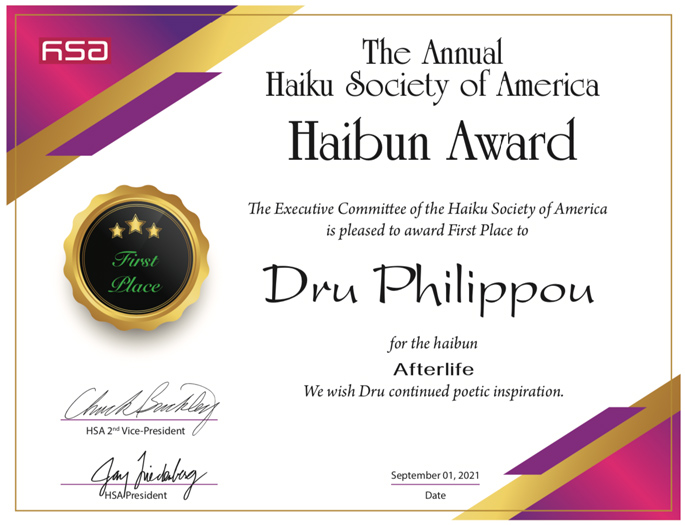

First Place:

by Dru Philippou, New Mexico, USA

Afterlife

I always take good care of them, removing the laces and brushing off the dirt with a soft bristle brush. Applying beeswax paste with the back of a spoon, I smooth it into the leather cracks until their espresso color revives. I give the gusseted tongue special attention, reaching those hidden places, and opening the boots fully to air.

resting

under a bristlecone pine . . .

weighing my optionsI wear them after the traction is gone, trying to beat out a few more miles although I can feel every rock, every stick through the rubber. On rainy days, the mud sucks them off my feet. The paleness at the toes reminds me of all those steps kicked into the slopes. They are holey, misshapen, speckled with guano, but I don’t want to let them go. At one point, I even re-glue the parting sole.

boot planter

the heavenly blue

of rambling lobelia~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

Prose: “Afterlife” begins with activity: the loving care given to the boots. Each prose segment ends with a strong image. “Opening the boots fully to air” resonates in the final haiku when we learn that the boot has become an outdoor planter. Word play on the phrase “parting sole” brings to mind “departed soul.” The spare and focused description of the boots evokes all our senses.

Haiku: After the activity of the prose, the first haiku begins with “resting” which takes place in an outdoor setting. Bristlecone pine, known for its long life in harsh conditions, is an excellent choice of tree. “Weighing my options” refers to the writer’s indecision—whether it’s to get rid of the boots or deciding which way to go. The final haiku offers a surprising shift—the metamorphosis of the boot into a planter. Once again being of service, but now to the beautiful (“heavenly blue”, hinting at an afterlife) lobelia. Lobelia is a climbing plant and the boot enables it to ramble, as it once did for the owner.

Title: “Afterlife” intentionally misleads the reader to imagine a person, when it’s actually about the life (and afterlife) of a boot. This succinct one-word title is perfectly chosen to illustrate its meaning of “a period of continued or renewed use”.

Second Place:

by Barbara Sabol, Ohio, USA

Roulette

When I was nine, our extended family traveled to visit my great aunt and uncle. My cousin, Mary Ann, a year younger, and my best friend, explored the house with me—closets, storage cubbies, basement recesses.

cloud cover

hollowing into the bole

in Pop’s old oakI drew open the top drawer of a large bureau in the bedroom we shared. Under a chamois cloth lay a pistol. Large, black, gleaming. The curved handle shaped to a palm’s grip.

Wide-eyed, we looked at each other. I reached in and lifted it. The gun’s unexpected weight in my small hand yanked my arm. Then the shot. A throbbing silence spread in concentric circles.

Even when my uncle came running naked from the shower, shock-faced, yelling, I heard only the bullet’s echo. Mary Ann and I stood frozen. The gun in a slow spin between us on the hard wood floor.

after the storm

the whip crack of thunder

pulses the air~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

Prose: The opening prose establishes the young girls’ innocent search for adventure and their fascination for the forbidden. The drama unfolds in cinematic scenes of discovery, leaving us to wonder what they will find next. Once they find the gun, we know from Chekhov’s dramatic principle that it has to go off. And it does. The prose ends with the dropped gun spinning on the floor between the girls as we, too, hold our breaths.

Haiku: Both haiku are strong and can easily stand alone. The first one takes us outdoors to a hidden place in nature (the oak bole). This exceptional, haiku links both visually and emotionally to the dark, interior places the girls have explored in the house. It is also foreboding, foreshadowing what’s to come. In the final haiku, we are outside again, where nature’s own drama is taking place. That sound of the gunshot reverberates in the “whip crack” of thunder.

Title: Once again, a title that sets up an expectation and then surprises us. Roulette brings to mind a casino and a gambling game, people making bets on where the ball will drop. But once the gun goes off, the story takes on a darker context. Russian roulette. We know that one bullet’s already gone off—but is there another? Neither the girls nor the reader know, which adds to the suspense

Third Place:

by Jennifer Hambrick, Ohio, USA

Air

Sunset angles grays and golds on the sterile white walls. A thin plastic tube drapes off the bed and glows for a moment in the sinking light. Amid a cluster of drooping mylar balloons, a monitor keeps vigil in a mantra of beeps.

She lies napping in a deep slot, blankets billowed around her. Watching her chest rise and fall with each breath, I realize I’ve been holding my own breath in fear. What must her life have been like? Ninety-four years of bouncing babies and wiping noses and cooking meals, of baking casseroles for church potlucks and organizing bake sales, of knitting Christmas stockings and making birthday cakes and going to her children’s weddings and their children’s weddings and bouncing more and more babies through the generations. It’s unfair, cruel even, that all of it—every tear wiped and skinned knee kissed, every family photograph and precious moment, all that love and time and, heaven help her, patience—must come to this withered evening in an overheated hospital room.

dusk

snipping the last thread

of the story quiltHer eyes open, flicker a few times, then land on me. I stand up from the Naugahyde lounger and step to the side of her bed.

“You had a nice snooze there, Gran,” I say, wiping the tears that rim my eyes. “How are you feeling?”

She jerks her head up off the pillow.

“Are you still here?” she blurts. “What are you still doing here? What am I still doing here?”

I watch gape-mouthed as she drops back down onto the pillow and rocks her head from side to side.

“Jeez-o-Pete, let’s get on with it,” she croaks. “I never thought I’d be alive this long.”

end of autumn

a child lets go

of a balloon string~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

Prose: “Air” begins with a depressing scene of a sick room, watching a grandmother sleeping as dusk falls. The description is a bit long and repetitive, but perhaps it’s meant to illustrate her long and ordinary life. The prose comes alive with the dialogue between the speaker and the dying woman—the irony of her asking “Are you still here?” and the outdated expression “Jeez-o-Pete,” illustrate the personality of this still-feisty woman.

Haiku: The “story quilt” is finished as the grandmother’s story comes to an end. An apropos haiku, as quilts are often made for hospice patients to comfort them in their final days. Evidently someone made a quilt with remembrances of her long life. The “drooping balloons” in the sickroom at the beginning are finally released into the sky, a metaphor for the grandmother’s release from suffering and the speaker’s letting go as the haibun comes full circle.

Title: Air appears throughout the haibun: as a plastic oxygen tube, in the rise and fall of the grandmother’s breath, the held breath of the narrator, and, at the end, as the as the air that carries the balloon into the sky. Good example of how a mundane title can expand its meaning through well-written prose and haiku.

Honorable Mention:

by J Hahn Doleman, California, USA

Dragon Boat

“Stretch out!” The drummer’s elongated vowels sweep across the water, her voice filling the humid air. Bending forward with arms extended, I plunge my paddle into the lake. Somewhere beneath us swims the spirit of exiled Chinese poet Qu Yuan.

sweet sedge swirls

in the churned up mud

my reflection“Reach for it!” The drummer’s job is to keep the rhythm flowing, to ensure an equal balance of power. The team’s objective is to hover the hull just below the waterline while propelling it forward. A difficult task when loaded down with 22 bodies, each weighing between 120 and 250 pounds. “Stroke! Stroke! Stroke!”

warm breeze

a damselfly floats

across our bow“Lift! Pull! Lift!” All around me my teammates are a blur of heads and torsos. We draw our handles along the gunwales, gouging perfect furrows into the surface, then raise our blades straight up and out of the water, only to repeat the cycle, over and over, long after our shoulders go numb. “Dig in! Deeper!”

shimmery shore

the form of a cormorant

drying her wings“Paddles up!” When the drummer finally gives the call to rest, there is an eruption of whoops followed by sighs and laughter from everyone. As our wooden skiff slips past a pocket of reeds, I listen to the ripples recede and expand and watch the wake behind us fold back into itself.

gliding through

the reflection of sky

a golden carp~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

This haibun shows the contrast between the effort expended by humans to move through water and the tranquility of the natural world around them. The haiku mark the stages in this progress, more of a dragon boat practice than a race. If one were to read this as a metaphor for life, rowing until “the drummer finally gives the call to rest.” It’s refreshing to see it as a practice rather than a race to the finish line. The ending gesture unfolds beautifully, the ripples recede, the wake folds into itself, and a golden carp glides through a reflection of sky.

Honorable Mention:

by Matthew Caretti, Pennsylvania, USA

Hungarian Rhapsody

I arrive in Budapest. Just before New Year’s Eve. But the pandemic has taken its toll. Instead of fireworks, chimney smoke. We wake to the sag of wet confetti. Decide on a walk to shake out the remaining cloud of palinka.

noon bells losing count of the steeples

On the way out, we pocket spare coins for the beggars. Head to the underground. Just one old man in the car. Reading the Bible. Then up St. Gellert’s Hill. Lichen on rock provides an old map of the new city. A distant streetcar moves amber into twilight clouds.

winter rain shortcuts through the dark city

Weeks pass. Months. Then a warm wind through sere branches brings the hope of spring. We discover more parks during our urban treks. The city sun twisting an old birch into long shadows. Six million leaves on the elm. I lose count. Again.

after the snowdrops spring

We listen to Swan Lake. The Balaton becomes a thought. A reality, despite winter’s brief reprise. Some brave locals go for a polar bear swim, while their dogs demur. Even with the cold and the re-imposed lockdown, the business of ducks here is still afloat.

she points out mute swans mate for life

Mornings on the lake are still. Only swan bottoms bobbing. After the village stop, a train tilts toward tomorrow. Merges with a flock low over the lake. Pulls with it my thoughts. Of the almond blossoming and how her father moves to restore the old shaker.

tumbling down from the pine lithe shadows

All around there is renewed work. With the harvesting of thatch and the labor of spring moles. Basalt cobbles slick in spring rain lead to the vineyards. The tending. I rouse myself from this long slumber. Organize a bike. Late onto the path, I ride into my breath.

twilight language the slow roost of rooks

~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

The title immediately conjures Franz Liszt, but the rhapsodic nature of the prose— snatches of images, fragments stitched together—seems most akin to a Greek rhapsody. The monoku stitch the various prose blocks together across a winter and spring. The selected images, sensations, and memories at first function to show how the narrator is overwhelmed by Budapest, even losing count of steeples and leaves. In the second half of the haibun, the images show a more settled narrator, one who moves beyond the city and appears more comfortable in the countryside. The journey of a relationship also weaves throughout this. The narrator arrives in Budapest alone to meet someone. The haiku about the swans introduces some ambiguity. Are they mates for life or is the woman suggesting they become mates for life? In the final line of prose, the narrator rides off alone into his breath but, in the final haiku, there is a return to the idea of settling.

Honorable Mention:

by Marietta McGregor, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

What Hides Beneath

sparrow-pecked chisel cuts a thief’s cipher

Between my aunt’s house and an empty reservoir stands an electricity substation, its walls slung with liana tangles of high-voltage wires studded with insulators like exotic fruit. The whole thing drones, a steady low-voiced monotone. Beyond it, the reservoir lies hollow and echoing, its stone-flagged floor littered with broken glass, split tennis balls and other trash. Slime-green seepage graffities walls of monumental sandstone blocks quarried and shaped by convicts. A rusted metal ladder hangs by an arm from one side like a half-drowned swimmer. After school I hear shouts and pock-thwacks of balls bouncing off the reservoir’s walls. I ask if I can go and play too. My childless aunt and uncle are protective. No, they say—a bad place. The reservoir once held water pumped from Hobart Rivulet for a prison settlement. Until British troops dispossessed and slaughtered Tasmania’s Palawa people, the stream was for thousands of years a migratory trail and fresh water source for the South East Mouheneenner band.

as if yearning to belong bunched catkinsSome days we walk along Cascade Road. Sparks crackle from overhead wires of trolley buses that trundle past the substation, making us jump. In English cottage gardens shaded by silver birch trees, climbing Black Boy roses blossom purple-bruise dark over white picket fences. At nightfall when buses stop the valley goes silent, save for downslope winds off Mount Wellington keening like lonely ghosts in the substation’s lines and transformers. Fast forward half a century. Electric trolley buses are gone, substation demolished. A badminton centre rises over the reservoir’s shell. Its concrete vault resounds to grunts and pop-pops of whacked shuttlecocks. But the reservoir has the last say. Rising damp warps the playing courts’ floors. The sports centre closes. There’s talk of a rebuild with a viewing window onto the colonial sandstone walls. An interpretive display highlighting the skills of convict masons. No mention of the Mouheneenner. No one says genocide.

bare winter skies a high tension of ravens

~ ~ ~

Comments from the Judges

A rich meld of a childhood memory of a place and the Tasmanian history that

contextualizes it. The childhood memory is dropped halfway through the second prose block as the narrative leaps fifty years into the future and rushes somewhat to the final word, “genocide”, a word no one wants to utter in reference to the “dispossessed and slaughtered . . . Palawa people.” The writing is strong and the title clearly relates to the theme of the reservoir below, literally by the dampness which rises to thwart the “progress” represented by a badminton centre, and figuratively by the colonial past represented by the “thief’s cipher” in the opening haiku and the “skills of convict masons.”

About the judges:

Margaret Chula’s books Grinding my ink and Shadow Lines (linked haibun with Rich Youmans) have received HSA Merit Book Awards. Her recent haiku collection, One Leaf Detaches, was awarded the Haiku Foundation’s Touchstone Distinguished Book Award. Her haibun, “Well of Beauty”, received the Grand Prix in the 2014 Genjuan International Haibun Contest. Maggie was a co-organizer for the HNA conference in Portland, Oregon, and served for five years as president of the Tanka Society of America.

Bob Lucky, erstwhile editor of Contemporary Haibun Online, is author of Ethiopian Time, Conversation Starters in a Language No One Speaks, winner of a James Tate International Poetry Prize, and My Thology: Not Always True But Always Truth. He lives in Portugal, where he's learning to swallow vowels and choke on sibilants..